"Rice Breast" Disease in Puddle Ducks

At the February 6, 2017 SSWA meeting, one of our members (Ben Sohm) raised the issue of his finding “rice breast” disease in local black ducks in ever increasing numbers in recent years. He also pointed out that the likely local culprit in all of this is the raccoon. To understand why this may be so, I decided to revisit this topic. (My original article on Sarcocystis was published in the September 2010 edition of the SSWA Newsletter.)

When hunters notice an abnormality or apparent disease in wild game they are preparing for consumption, they naturally have questions regarding their observation—particularly how it might affect their own health or the health of people consuming the meat.

BELOW IS A PHOTO SHOWING THE SKINNED CARCASS OF A DUCK INFECTED WITH SARCOCYSTIS. PROBABLY A GOOD ARGUMENT FOR SKINNING YOUR BIRDS.

What is it?

Sarcocystis is a parasitic infection caused by a proto-zoan (single-celled organism). Some species of Sarco-cystis can cause illness in certain animals. However, waterfowl affected with this disease usually do not look or act sick and generally the disease is not fatal. Occasionally, severe infections may cause muscle loss with resultant lameness or weakness. Such affected birds may be more susceptible to predation.

How do I know if my duck has this disease?

You won’t usually see external evidence of Sarcocystis infection. However, once you skin the bird, you can easily recognize the visible form of the disease—you will see cream-colored cylindrical cysts running in parallel lines throughout the muscles. Since cysts are located in muscles, hunters who pluck birds without viewing the meat may miss the disease.

Because these cysts resemble rice grains, Sarcocystis is commonly called “Rice Breast Disease.” The cysts usually occur throughout the skeletal muscles in the breast and thighs, but may also occur in the heart or smooth muscle of the digestive tract. Deposits of minerals around the cysts enhance their visibility and may feel gritty when you cut the muscle with a knife.

Sarcocystis appears to take time to develop visible cysts, so juvenile birds rarely show any signs. In years of poor duck production, hunters may bag more adult ducks and thus be more likely to notice infected birds. What animals are affected? A wide variety of birds, mammals, and reptiles can contract Sarcocystis. Among waterfowl, dabbling ducks (mallard, pintail, shoveler, teal, black duck, gadwall, and widgeon) are the species most commonly affected with the visible form of the disease. Diving ducks are only occasionally affected.

How do they get it?

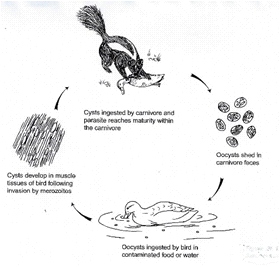

Waterfowl and other animals become infected with Sarcocystis by ingesting the eggs of the parasite in food or water. The parasite requires a primary host (carnivore) and a secondary host (waterfowl and other herbivorous animals) to complete its life cycle. In the primary host’s intestine, the parasite matures and produces microscopic eggs. The eggs pass out in the carnivore’s feces, contaminating the environment. Waterfowl ingest the eggs while feeding. When the eggs hatch, the parasites move through body tissues to the skeletal muscles where they form cysts. The cycle is completed when a carnivore consumes prey infected with Sarcocystis.

THE DIAGRAM BELOW SHOWS A SKUNK AS THE PREDATOR. HOWEVER, ON LONG ISLAND, THE MOST LIKELY PREDATOR WOULD BE THE RACOON (AND POSSIBLY THE FOX.)

Ben reported seeing lots of racoons in the marsh where he hunts. As you can see from the diagram, Ben is probably correct about the racoon being the guilty party in all of this.

We don’t know a lot about the life cycles of most species of Sarcocystis. Currently it appears that each type of Sarcocystis prefers specific primary and secondary hosts. This means that different carnivores are involved in the infection of different waterfowl, and may explain why only certain species of waterfowl are infected in some areas.

Can it be controlled?

No methods currently available will control the disease in wild waterfowl, nor is the need for this control seen, from a biologist’s point of view. This is because Sarcocystis rarely kills waterfowl directly. To control the parasite, we would have to interrupt its life cycle, which would require a thorough understanding of specific carnivore to waterfowl species interactions. (This information, and the development of control measures, would be more useful in captive waterfowl.) However, in specific locations, with specific predators, predator control may in fact have a positive impact. Even though studies show that the most likely locations for this are the breeding grounds, racoon control in the local black duck marsh just may have a beneficial effect.

Is Sarcocystis a threat to me or my animals?

We are told that Sarcocystis found in waterfowl presents no known hazard to humans and is not known to be transmitted to humans. Proper cooking destroys all forms of the parasite; however, hunters usually discard unappetizing carcasses containing large visible cysts. Other species of Sarcocystis (S. hominis, S. porcihominus) infect cattle and pigs, respectively, and can be transmitted to humans who eat undercooked meat. Dogs can be the primary host for at least seven species of Sarcocystis, with elk, mule deer, cattle, horses, pigs, and sheep acting as secondary hosts; but infection does not cause disease in dogs or other domestic animals. Sarco-cystis species commonly found in waterfowl have not been shown to infect dogs or other domestic animals. However, because dogs are susceptible to at least some species of Sarcocystis, it is not recommended to feed uncooked infected waterfowl to domestic animals. Remember, if you cook the meat, you kill the parasite.